SIディベート:トランプ政権2期目1年間の気候変動投資

2015年のパリ協定以降、低炭素型の企業は高排出の企業より投資成果が良好なのかという点は、投資家、政策担当者、研究者の間で大きな論点となっています。この比較は単純に見えますが、実際には期待、リスク、政策、資本コストが複雑に絡み合う構造が存在します。表面的には、世界的な温暖化への関心の高まりやクリーンエネルギー移行が進むほど、低炭素企業の方が成長期待は高くなるように見えます。

まとめ

- トランプ政権2期目は、気候変動投資を取り巻く状況に変化をもたらしています。

- 米国の政策転換により、排出量の多い企業(ブラウン企業)は短期的には追い風となりました。

- 一方で、気候変動の対策に積極的な企業(気候変動リーダー)は、遅行企業(ラガード)に対して依然として相対的に良好な実績を示しており、利益見通しの改善がその背景にあります。

一見すると、この考え方は直感的に受け入れられるものに見えます。世界が地球温暖化への懸念を強め、クリーンエネルギーへの移行を受け入れ始めている状況であれば、低炭素型の事業を展開する企業は、より良好な成長機会を得られると考えるのが自然だからです。そして実際、グリーン企業の株式がブラウン企業を上回っていた局面がある理由のひとつは、比較的明確であり、利益に対する市場の期待に関係しています。

投資家は、グリーン関連技術がどれほど急速に発展し、需要がどれほど大きく変化するかを十分に織り込んでいなかった可能性があります。こうした中で、利益見通しが上方修正されると、その修正を反映して株価は上昇しました。一方で、石油生産、石炭採掘、重工業といった高排出企業では、同じような前向きの見通し修正が比較的少なかった可能性があります。

しかし、ここにはもう一つ、より慎重に捉えるべきメカニズムが存在します。教科書の議論以外ではあまり注目されることのない「資本コスト」です。資本コストとは、投資家が企業の株式を保有する際に要求する期待収益率を指す概念です。この期待収益率が上昇すると、企業の事業内容が変わらなくても株価は下落します。

そして、ここで気候政策が重要な位置を占めることになります。大規模な機関投資家が化石燃料依存度の高い産業から投資を引き揚げる際、その理由としては倫理的な観点だけでなく、リスク要因も挙げられることが多くあります。高い炭素排出量を持つ企業は、より厳格な規制、将来的に投資回収が難しくなる可能性のある資産、需要の変動、そして将来の負債といった課題に直面します。

大規模な機関投資家が化石燃料に依存する産業から投資を引き揚げる際、その理由としては倫理的な観点だけでなく、リスク要因も挙げられることが多くあります。

これらのリスクを踏まえると、ブラウン企業はより高い資本コストを抱えるべき企業として市場で認識されやすくなります。投資家が保有を減らすと株価は押し下げられ、その結果として期待収益率は上昇します。

言い換えると、ブラウン企業の株式が劣後するのは、市場がそれらを保有したいと考えなくなることによるものであり、必ずしも企業の利益が低迷しているためとは限りません。皮肉なことに、こうした高い資本コストが市場価格に完全に織り込まれると、理論上は逆の効果が生じるとされています。すなわち、気候リスクが高いことの補償として、ブラウン企業は最終的により高い期待収益率を示すとされています。この関係性は、一部の研究者によって「カーボンリスク・プレミアム」と呼ばれています。

では、実際には何が起きたのでしょうか?

これを明らかにするため、研究者は株価と長期的な成長期待、さらに変化する資本コストを結びつける、より高度なモデルを構築してきました。ロベコがこれらのモデルを推計し、その結果を検証すると、状況の全体像が徐々に見え始めてきます。

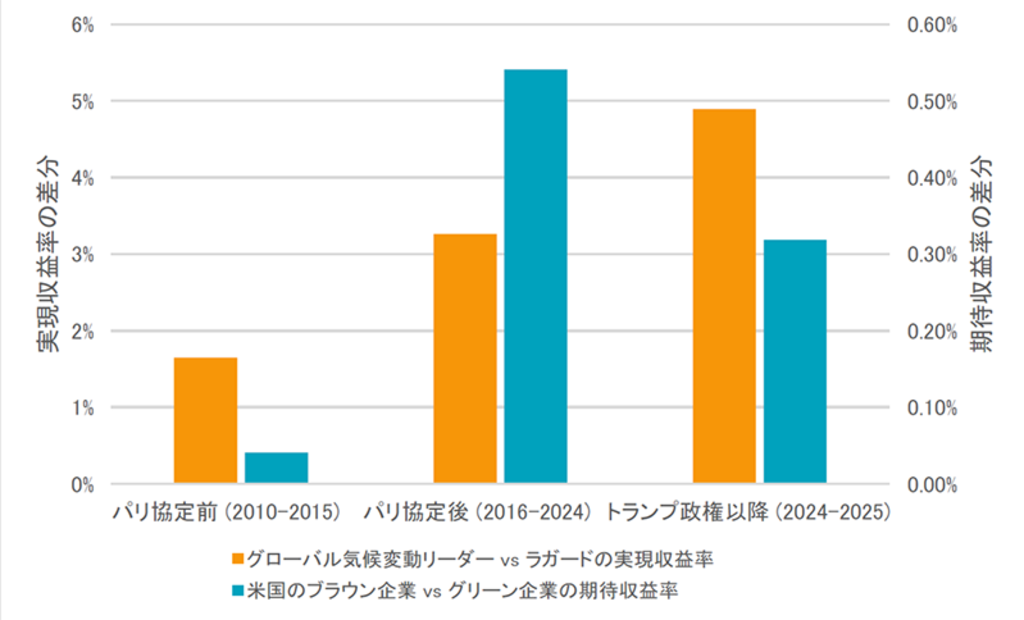

図1:期待収益率と実現収益率のパラドックス

過去の実績は将来の投資成果を保証するものではありません。投資対象の価値は変動する可能性があります。例示のみを目的としています。

出所:ロベコ, Markwat, Hanauer, Swinkels( 2026年)

米国では、パリ協定直後の数年間において、高排出企業(ブラウン企業)の資本コスト、すなわち期待収益率は、同業種内で低排出企業(グリーン企業)と比べて0.55パーセントポイント上昇したことが確認されています。ここでグリーン企業とは、各業種において炭素排出強度が最も低い上位3分の1の企業群を指し、ブラウン企業は最も高い下位3分の1に該当します。

この結果は上図の青色の棒グラフに示されています。これは金融市場における意味のある再評価であったと考えられます。そして注目すべき点として、このブラウン企業とグリーン企業の0.55パーセントポイントの差は、2024年11月の米国大統領選挙まで概ね維持されていました。

トランプ政権2期目:ルールの巻き戻し

その後、政治状況は転換しました。気候変動に関する規制は後退し、米国はパリ協定から離脱し、クリーンエネルギーへの補助金も削減されました。汚染負荷の高い企業に対する圧力は弱まり、投資家も同様の反応を示しました。トランプ政権は1期目でもパリ協定から離脱しましたが、2期目では気候変動政策の後退がより積極的に進められました。

その結果、ブラウン企業とグリーン企業の資本コストの差は縮小し、0.30パーセントポイントまで低下しました。ブラウン企業の株式を保有する投資家にとって、これは好材料となりました。資本コストが低下すると、企業価値は自動的に押し上げられるためです。実質的に、米国の政策後退は国内の高排出企業(ブラウン企業)にリターン面での押し上げ効果をもたらしました。

気候変動リーダーとラガード

ロベコでは、企業をグリーン企業とブラウン企業に単純に分類することはあまり重視していません。むしろ、企業が自社の事業を脱炭素化するための信頼できる計画を持っているか、またはクリーンエネルギー移行を加速させる新しい技術を開発しているかを評価しています。こうした計画を持つ企業を「気候変動リーダー」、そうでない企業を「気候変動ラガード」と呼んでいます。

米国の気候変動に対する取り組みが弱まる中でも、グローバルの気候変動リーダー企業では、利益見通しが改善する動きが確認されました。

両者の間には一定の重なりがありますが、この区別は重要です。ブラウン企業の中にも、実際にグリーン化に向けて信頼性の高い移行を進めている企業が存在するためです。しかし、これらの気候変動リーダー、すなわちグリーン企業やグリーン化を進める企業は、政策の後退によって影響を受けると想定されていたはずです。では、こうした「正しい取り組み」をしてきた企業は、不利な扱いを受けたのでしょうか。

データはその逆の状況を示唆しています。米国の気候変動への取り組みが弱まる中においても、グローバルの気候変動リーダー企業では、技術革新の進展、クリーンエネルギーコストの低下、そして欧州およびアジアでの気候変動に配慮した政策の採用が加速したことを背景に、収益見通しが改善する動きが確認されました。この結果は、図中のオレンジ色の棒グラフに示されています。こうした利益見通しの上方修正は、米国の政策動向に左右されることなく株価に反映されました。

それは報われたのか?

では、グリーン化の取り組みは報われたのでしょうか。これは、どのように評価するかによって結論が異なります。米国では、気候変動政策の後退によりブラウン企業が短期的に追い風を受けました。しかし、グローバルの気候変動リーダー企業では、依然として予想を上回る成長が確認されています。

明らかな点として、パリ協定以降の市場の動きは、クリーンエネルギーが単純に勝利したという話ではなく、より複雑な構造を持っています。市場の期待の変化、地政学的な政策転換、リスク再評価の進行、そして金融市場における気候変動がもはや抽象的な将来懸念ではないという事実を示す状況が背景にあります。気候変動対応は、すでに今日の市場価格に影響を及ぼしています。

SIディベート

重要事項

当資料は情報提供を目的として、Robeco Institutional Asset Management B.V.が作成した英文資料、もしくはその英文資料をロベコ・ジャパン株式会社が翻訳したものです。資料中の個別の金融商品の売買の勧誘や推奨等を目的とするものではありません。記載された情報は十分信頼できるものであると考えておりますが、その正確性、完全性を保証するものではありません。意見や見通しはあくまで作成日における弊社の判断に基づくものであり、今後予告なしに変更されることがあります。運用状況、市場動向、意見等は、過去の一時点あるいは過去の一定期間についてのものであり、過去の実績は将来の運用成果を保証または示唆するものではありません。また、記載された投資方針・戦略等は全ての投資家の皆様に適合するとは限りません。当資料は法律、税務、会計面での助言の提供を意図するものではありません。 ご契約に際しては、必要に応じ専門家にご相談の上、最終的なご判断はお客様ご自身でなさるようお願い致します。 運用を行う資産の評価額は、組入有価証券等の価格、金融市場の相場や金利等の変動、及び組入有価証券の発行体の財務状況による信用力等の影響を受けて変動します。また、外貨建資産に投資する場合は為替変動の影響も受けます。運用によって生じた損益は、全て投資家の皆様に帰属します。したがって投資元本や一定の運用成果が保証されているものではなく、投資元本を上回る損失を被ることがあります。弊社が行う金融商品取引業に係る手数料または報酬は、締結される契約の種類や契約資産額により異なるため、当資料において記載せず別途ご提示させて頂く場合があります。具体的な手数料または報酬の金額・計算方法につきましては弊社担当者へお問合せください。 当資料及び記載されている情報、商品に関する権利は弊社に帰属します。したがって、弊社の書面による同意なくしてその全部もしくは一部を複製またはその他の方法で配布することはご遠慮ください。 商号等: ロベコ・ジャパン株式会社 金融商品取引業者 関東財務局長(金商)第2780号 加入協会: 一般社団法人 日本投資顧問業協会