Losing money with passive investing

Passive investing may be popular, but it also raises serious concerns. In particular, it means getting exposure to stocks that not only don't add to performance, but actually have a negative impact on it.

概要

- Passive investing means assuming the CAPM works

- But the CAPM has a very poor empirical track record

- A better approach to is use a multi-factor ranking model

A century of empirical evidence shows that although equities exhibit high volatility in the short run, they are rewarded with a higher return than bonds and cash in the long run. In order to capture this so-called equity premium, many investors have an allocation to equities in their strategic asset mix.

An increasingly popular way to earn the equity premium in practice is by replicating a broad capitalization-weighted equity market index which serves as a good proxy for the theoretical equity market portfolio. Such a passive investment approach allows investors to earn the equity premium at a minimal cost. It also takes into account that more expensive actively managed funds have failed to outperform as a whole, although that is not surprising given that active investing is a zero-sum game before costs, and a negative-sum game after costs.

Passive investing boils down to investing a little bit each in thousands of individual stocks. These thousands of investments combined should earn investors the equity premium. But does each of these individual stocks really help you capture the overall equity premium? The answer could be yes if the expected return premium for every stock were the same and equal to the overall equity premium.

In that case, however, investors would be better off investing in a minimum volatility portfolio, as that would allow them to earn this expected return premium with the least risk. The literature on minimum volatility strategies shows that it is not very difficult to create a portfolio which is less risky than a broad capitalization-weighted market index. Clearly, therefore, passive investing in a broad market index is not a logical course of action if one expects every stock to have the same expected return.

So which assumption would justify passive investing in a broad capitalization-weighted market index? The above implies that at the very least, one must assume that certain stocks have higher expected returns than others. More specifically, if one assumes that the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) holds, it can be shown that the market portfolio is, in fact, the optimal choice for investors. The CAPM postulates that the expected return on a stock is proportional to its level of systematic risk, or beta. In other words, a stock that is half as risky as the equity market portfolio should earn only half the equity premium, while a stock that is twice as risky as the equity market portfolio should earn double the equity premium.

Passive investing means assuming that the CAPM works, but is that a reasonable assumption?

So passive investing according to a broad capitalization-weighted index is justified, assuming that the CAPM works, but is that a reasonable assumption? Based on the popularity of the CAPM in standard finance textbooks, one might be inclined to think that it is. Empirically, however, the model has a very poor track record. Studies which have tested the predictions of the CAPM using real data have failed to find a positive relationship between systematic risk and stock returns. The actual relationship appears to be flat, or even inverted, i.e., if anything, riskier stocks tend to generate lower rather than higher returns.

Whereas systematic risk turns out to be a poor predictor of future expected stock returns, various other stock characteristics, such as the size, valuation, momentum and quality features of a stock, have been found to be powerful indicators of future expected returns. Models which include a combination of such factors have effectively replaced the theoretically elegant but empirically disappointing CAPM. Examples of such models are the three-, four-, and five-factor models of renowned professors Fama and French, and others.

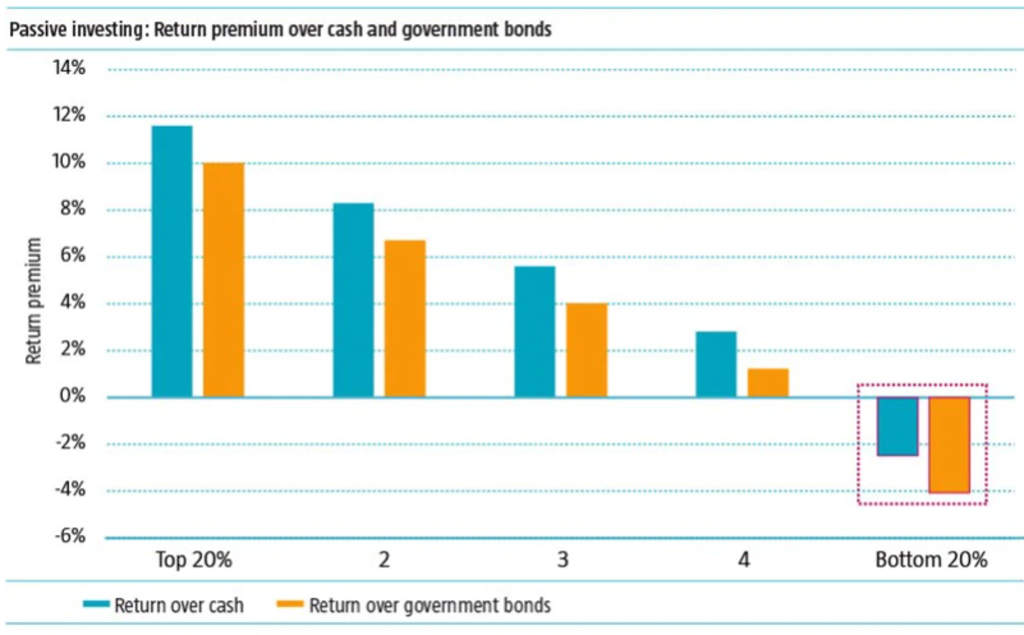

What do these widely known insights imply for the expected return of individual stocks? In order to answer this question, we created a simple model, inspired by the literature on which characteristics drive stock returns. Specifically, we ranked stocks, dividing them into five groups every month, based on their total score in terms of a combination of commonly used value, momentum, quality, and low volatility factors. Next, we looked at the performance of these five portfolios from 1986 to 2016, which is the longest period for which we have data on global stocks. The figure below shows that our simple model is highly effective at separating stocks with high average returns from those with low expected returns.

Particularly interesting is the finding that the 20% of the stocks with the least attractive factor characteristics generated a negative premium over period of more than thirty years, amounting to minus 2.5% per annum versus cash, and even minus 4% per annum versus high-grade government bonds. If all stocks earned a positive premium at the very least, one might still shrug off the whole discussion about factor characteristics by arguing that although some stocks may have lower returns than they ought to, they do at least still contribute positively to performance.

These results, however, show that a significant portion of a passive portfolio is actually invested in stocks which contribute negatively to performance. Next time you hear someone arguing that passive investing is a prudent approach, think twice about that. And bear in mind that the model which we used here to rank stocks is still quite simple. Quant asset managers such as Robeco have developed more sophisticated models which show an even bigger return spread between attractive and unattractive stocks.

Source: Robeco

What is the intuition about these results? Well, taken together, stocks may earn a healthy premium, but that does not mean that every stock individually can be assumed to do so. In particular, if a stock is expensive based on straightforward valuation multiples such as P/E, is in a downtrend, has low profitability, and is also very risky, then decades of historical data tell us that such a stock should not be expected to deliver a positive, but rather a negative premium. Passive investors, however, choose to ignore this evidence, and happily invest in stocks with such a deadly cocktail of characteristics just as they do in any other stock.

Passive investing leads to inefficient portfolios

Proponents of passive investing might counter that they are neither believers nor disbelievers in factor premiums. If all you can be reasonably sure about is that there is a long-term equity premium and you are agnostic about the existence of factor premiums, isn’t passive investing a sound approach? The problem with this argument is that the investment choices one makes point to certain implicit views, or ‘revealed preferences’ as economists call them.

Investing passively in the capitalization-weighted index means that one implicitly assumes that a model such as the CAPM holds, and that the factor premiums which have been observed in historical data are either not exploitable in real life, or will no longer materialize in the future, e.g. because they were a mere historical fluke or have by now been arbitraged away. Clinging to a theoretical construct from the 1960s and simply dismissing everything we have come to know about stock returns since then is not prudent, but seems more like wishful thinking, an intentionally contrarian strategy, or denial of inconvenient facts.

So, passive investing means putting a significant chunk of the portfolio in stocks which have a negative expected premium, i.e. which not only do not add to performance but actually have a negative impact on it. But what are the investment implications of this insight? In other words, if investors do not want to suffer passively due to stocks that only cost them money, what can they do instead? One alternative would be to invest passively in all stocks, except, for instance, the 20% of stocks with the least attractive factor characteristics.

That is not as easy as it sounds though, because factor characteristics of stocks are not constant but are continuously evolving. This means that the 20% of stocks that are least attractive this month will be different from next month’s 20%. Since factor characteristics do not change drastically overnight, one does not need to completely reconstitute the portfolio all the time, but still, active maintenance is required, and this involves some periodic turnover.

A more efficient approach is to not only avoid the least attractive stocks according to a multi-factor ranking model, but to also invest the proceeds in the most attractive stocks according to the model. These stocks not only exhibit the highest expected return based on their factor characteristics, but are also the ones that are least likely to drop down to the worst category in the near future, which helps to save turnover. Our enhanced index and factor index strategies are based on such principles, and are specifically designed to avoid the pitfalls of passive index strategies. For more information on our efficient alternatives to passive investing, please contact your local Robeco client relationship manager.

Important information

The contents of this document have not been reviewed by the Securities and Futures Commission ("SFC") in Hong Kong. If you are in any doubt about any of the contents of this document, you should obtain independent professional advice. This document has been distributed by Robeco Hong Kong Limited (‘Robeco’). Robeco is regulated by the SFC in Hong Kong. This document has been prepared on a confidential basis solely for the recipient and is for information purposes only. Any reproduction or distribution of this documentation, in whole or in part, or the disclosure of its contents, without the prior written consent of Robeco, is prohibited. By accepting this documentation, the recipient agrees to the foregoing This document is intended to provide the reader with information on Robeco’s specific capabilities, but does not constitute a recommendation to buy or sell certain securities or investment products. Investment decisions should only be based on the relevant prospectus and on thorough financial, fiscal and legal advice. Please refer to the relevant offering documents for details including the risk factors before making any investment decisions. The contents of this document are based upon sources of information believed to be reliable. This document is not intended for distribution to or use by any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country where such distribution or use would be contrary to local law or regulation. Investment Involves risks. Historical returns are provided for illustrative purposes only and do not necessarily reflect Robeco’s expectations for the future. The value of your investments may fluctuate. Past performance is no indication of current or future performance.