Volatility strikes in the UK bond market

Per le nostre strategie fixed income aggregate vediamo opportunità sullo yield dei titoli investment grade in sterline.

Résumé

- Bank of England steps in to avert an LDI crisis

- Active quantitative tightening might have to wait

- Buying opportunity emerging for sterling investment grade credit

Developments in the UK have in recent weeks induced further volatility in global bond markets. Since 22 September, 30-year UK Gilt yields have traded in a 200 bps range, first rising very sharply after the new government delivered its mini-budget, only to reverse half of that following the announcement by the Bank of England (BoE) that it would intervene in the long-dated Gilt market to ease volatility.

The announcement of large unfunded tax cuts without any supplementary calculations or scrutiny from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) prompted investor concerns about how they would be financed. This led to the largest sell-off in long-dated Gilt yields on record, while briefly putting downward pressure on sterling and prompting wider credit spreads.

Volatility in the long end of the Gilt yield curve was exacerbated by issues in the liability-driven investment (LDI) market, where Gilts and other assets classes have been sold to satisfy near-term liquidity needs. This effectively disrupted the normal functioning of the ‘risk-free’ segment of the government bond curve, threatening financial market stability.

Indeed, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence in the media of LDI investors who were unable to meet collateral and liquidity requirements, and whose forced selling triggered downward spirals in markets. Long-end Euro and UST bond yields also increased sharply as a result; credit spreads widened, equities fell and cyclical FX traded down sharply. In short, volatility struck again!

These developments have raised questions around the UK’s debt sustainability and even concerns about the possibility of an emerging market-style currency crisis. These are not justified, in our opinion. First, the UK’s debt metrics contradict such worries, with its debt-to-GDP ratio being slightly lower than that of many of its developed market peers and its average debt maturity being much longer – a healthy feature from a refinancing perspective.

Secondly, the UK government was relatively fast to shift its tone in a way that provided some assurance to markets, albeit without making a complete policy reversal. Indeed, over the weekend after the announcement of the mini-budget the Prime Minister acknowledged that it should have been handled differently, and on 3 October the decision to reduce the 45% tax rate was reversed. Furthermore, the government has pledged involvement of the OBR in the budget process going forward, which we see as a good sign.

Active QT might have to wait

The BoE held its last policy meeting one day before the mini-budget announcement and its actions since then seem to suggest they were surprised by the size of the mini-budget and the subsequent market reaction. In a split vote during that meeting, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) decided against a 75 bps hike and increased the bank rate by just 50 bps to 2.25%, with the MPC’s newest member, Swati Dhingra, voting for just 25bps. The BoE also announced a plan to actively sell government bonds, starting on 3 October, as part of its quantitative tightening (QT) policy.

Following the mini-budget announcement, a brief BoE statement on Monday 26 September failed to assure markets. Finally, on Wednesday 28 September, the BoE was forced to intervene and purchase government bonds to stabilize the long end of the Gilts curve, while postponing the start of its active sales program to 31 October. The size of the latter was left unchanged. The intermediate intervention (on “whatever scale is necessary”) was seen as a necessary response to rising financial stability risks.

Gilt yields have come down significantly since the intervention but are still at elevated levels, signaling that markets expect the BoE will be forced to hike the bank rate more than had been expected before the mini-budget. Indeed, (structural) fiscal easing at a time of very high inflation calls for an even more aggressive monetary tightening path. This is exacerbated by the current account dynamics which should lead to a bit more upward pressure on yields and/or downward pressure on sterling.

Currently, peak interest rates of around 5.25% are priced in versus a neutral interest rate estimate of 2%. We think that these kind of interest rates could really ‘break’ the UK economy, by potentially triggering a deep recession. We anticipate the BoE could hike rates by 75 bps in November and 50 bps in December. For 2023 as a whole we expect another 100 bps in hikes cumulatively, but frontloaded in Q1. Given that the government has backtracked somewhat in both the content and optics of its fiscal plan, we think that it is unlikely that the BoE will deliver an intermeeting hike in October.

We expect the BoE’s market intervention program to become a permanent measure. For now it has committed to intervene in the long-dated Gilt market until 14 October and to start active Gilt sales on 31 October. Selling Gilts would speed up the balance sheet shrinkage and would tighten monetary policy, as desired by the BoE, but it would also deliver more Gilt duration to the market at the same time that government is planning to issue additional Gilts to fund the fiscal easing.

The combined effect of this would be a rise in the net supply of Gilts to unprecedented levels, risking some additional risk premia in Gilts. But given their resolve to maintain financial stability and to reduce dysfunction in the Gilt market, it seems unlikely that the BoE would start to actively sell Gilts on 31 October. Instead, it could be forced keep the threat of intervention alive to prevent dysfunction in the Gilt market. At the same time, we expect the BoE to continue its passive QT program (e.g. no reinvestments of maturing bonds), although we question how long this can be the case given the UK is slipping into recession, which is forcing the BoE to slow its pace of tightening.

Buying opportunity emerging for sterling investment grade

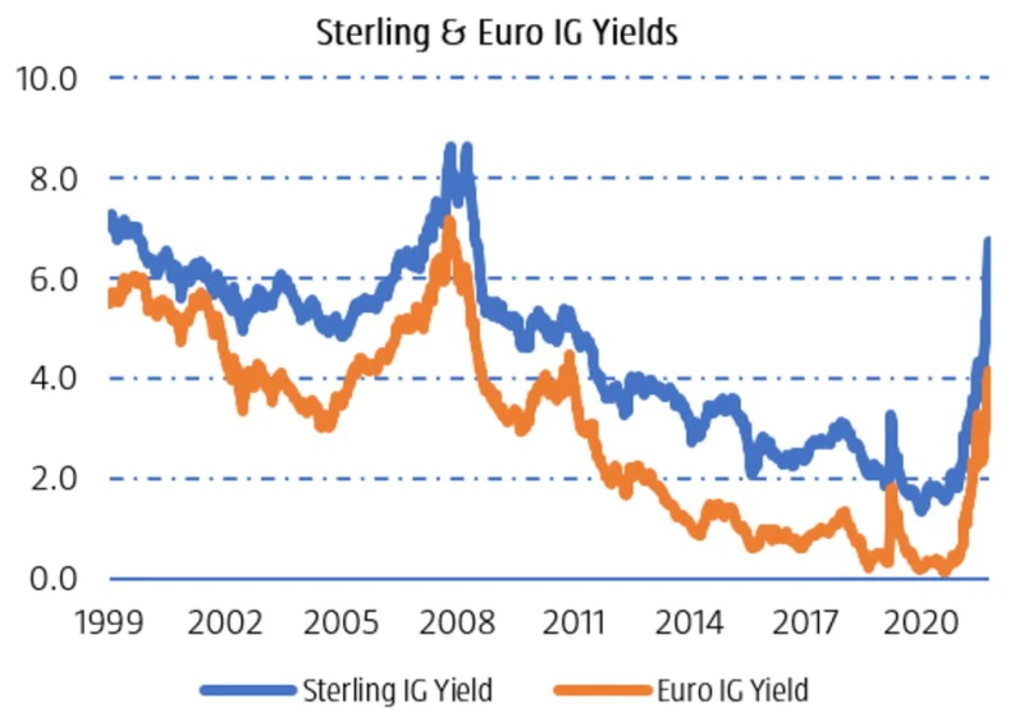

Volatility and sharp swings in sentiment create opportunities. We think an opportunity to buy sterling investment grade (IG) corporate bonds outright has arrived, as yields have reached levels seen only once in the past 20 years – during the worst throes of the GFC. The volatility following the mini-budget has pushed not only Gilt yields up but credit spreads wider. As a result, sterling IG yields are currently trading with a 6% handle, which is cyclically very attractive compared to history.

Two components combine to make these valuations attractive: first, Gilt yields are over +300 bps higher year to date in 2022; second, sterling IG spreads have widened to levels only 40 bps below their Covid highs in 2020. Taken together, these mean sterling IG yields have risen nearly 500 bps since December 2021.

Figure 1 | Sterling investment grade credit

Source: Robeco, ICE Bofa; 5 October 2022

While we think sterling IG is attractive at a 6.75% yield for long-term investors, that is not the same assertion as saying that yields might not rise to 7 or 8%, as they did in 2008. Tail risks from Russian nuclear escalation or a banking failure in Europe are obvious identifiable catalysts that could take us there. As with most value opportunities, we therefore prefer to scale into a position gradually. The good news is that we think the time to scale in, in sterling IG at least, has begun.