We’re ‘a big world on a small planet’ – the role of sustainability in finance

The world is consuming natural resources and polluting the environment beyond what the planet can reasonably manage. In the words of award-winning climate scientist, Johan Rockström, we are indeed ‘a big world on a small planet’.1 Sustainable finance can help forge a path to economic growth that is socially and environmentally fair for present and future generations.

Summary

- The world is depleting natural resources at a dangerous pace

- Population growth will exacerbate an already precarious position

- Finance can help channel capital to companies generating sustainable profits and growth

The rapid rise in industrialization, material wealth and consumption has blinded us to the fact that we live in a world of shared and finite resources. The Tragedy of the Commons is an apt metaphor for this dilemma. If common goods such as air, water and many of nature’s other services are available free of cost, they will be consumed indiscriminately by self-interested parties without regard for other stakeholders (in the present or future). As the global population approaches ten billion by 2050 and emerging countries demand Western living standards, the tragedy of the commons will only intensify.2

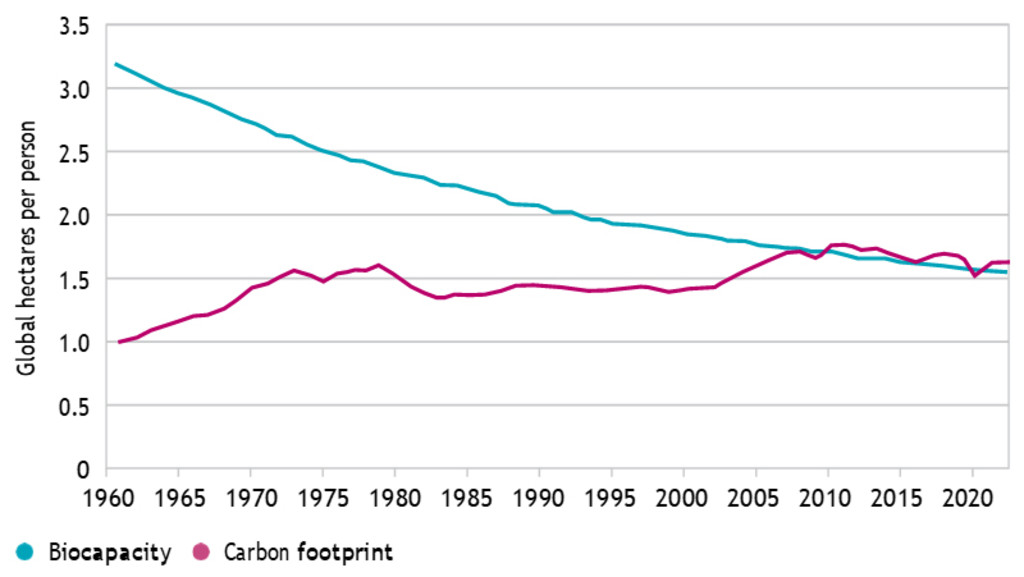

Research from the Global Footprint Network estimates that humanity is currently using natural resources 1.75 times faster than our planet’s ecosystems can regenerate them.3 This means that 1.75 Earths are needed to maintain current living standards, which is clearly unsustainable. If ‘business as usual’ scenarios continue, by 2050 three Earths will be needed to sustain the standards of living to which we have grown accustomed.4 The cost of this global ecological overspending is becoming increasingly evident in the form of deforestation, soil erosion, biodiversity loss, and the build-up of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Figure 1: The Earth’s biological productivity is in a decades’ long decline

World ecological footprint and biocapacity from 1961-2022 in global hectares per person. Biocapacity refers to nature’s ability to provide products and services for human demand and consumption including food, fibers, timber, energy production, carbon capture etc.

Source: Global Footprint Network, Overshoot Day Initiative. Earth Overshoot Day 2022 Nowcast Report.

The challenge for businesses and economies is to efficiently use Earth’s resources without depleting them. This will require a shift away from wasteful production-consumption models toward circular ones where resources are recycled, reused, and repurposed.

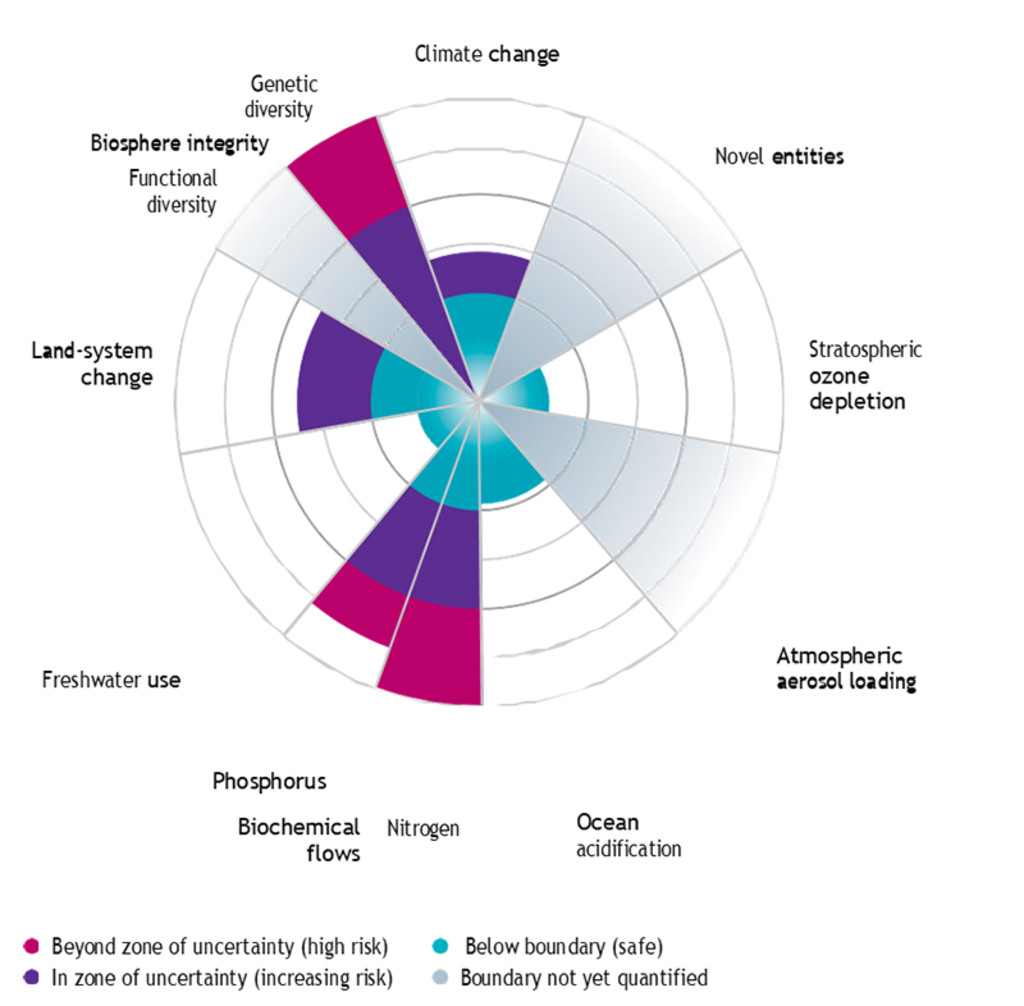

Figure 2: Science-based planetary boundaries

Source: Robeco, Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University. 2015.

Planetary boundaries

Resource scarcity is just one of a series of crises that must be addressed for humanity and the planet to survive and thrive. In 2009, a team of internationally renowned scientists introduced the Planetary Boundaries Framework which identifies nine critical processes that work in unison to regulate and stabilize life on Earth (see Figure 2). For each of these processes, the boundaries quantify the levels that are acceptable and safe for life on the planet.

Disturbingly, recent scientific studies show that human activity has already pushed us beyond the ‘safe zone’ and into states of ‘high uncertainty and risk’ for at least five out of nine of these critical maintenance systems, including climate change, biodiversity loss, vital nutrient flows, land use and novel entities (a group that includes plastics).5

The impact of climate change is already beginning to demonstrate that the risk of breaching these planetary boundaries for businesses and investors is large. They will cause scarcity of raw materials, supply chain disruptions, shifts in consumer preferences, increased regulation and more generally, higher costs overall.6

Accounting for social costs

Sustainability encompasses much more than preserving natural resources and ecological boundaries, it also aims to protect social capital.

The doughnut economy is a conceptual framework that offers a means of integrating the human element into frameworks dominated by ecological metrics. Much like the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), it recognizes that people on the planet should have access to life’s essentials, including food, shelter, education, and healthcare. In short, the framework maintains that sustainable economic development should not overshoot planetary boundaries or undercut human needs and well-being.7

More recently, a team of scientists combined the social aspects of the doughnut economy with the planetary boundaries to construct a set of new Earth System Boundaries.8 These are designed to minimize harm caused by boundary breaches on human health and well-being as well as to address issues of fairness and justice. In a 2023 report, the group revealed that when both human well-being and social justice factors are considered alongside planetary health, numerous boundaries have already been exceeded.9

Finance can play a key role

While direct government intervention can help ensure that economic prosperity is long-lasting, sustainable finance also has an essential role to play. It can help ensure that financial capital is efficiently allocated to companies that are making products in a sustainable way. Investors can use ESG scores to evaluate companies on a full range of sustainability factors – spanning everything from water quality, waste management, and carbon emissions to more social factors such as board diversity, talent retention and employee safety – all of which can impact a company’s competitive position and long-term financial performance (financial materiality).

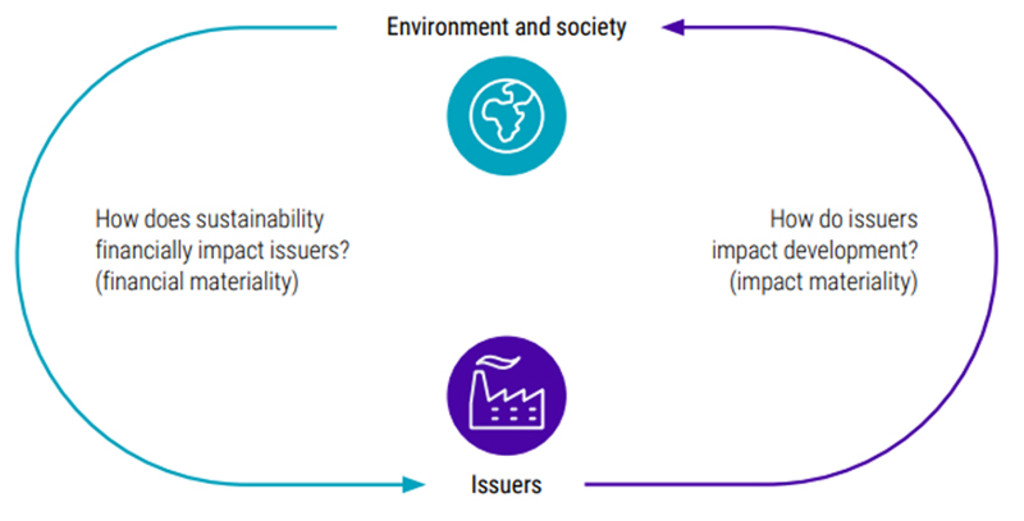

Next to assessing financially material issues to make better-informed investment decisions, regulators are now using the principle of ‘double materiality’ to measure a firm’s sustainability. Double materiality broadens the material scope of sustainability to include the impact of a company’s products/services on society and the environment (impact materiality). Measuring impact materiality is critical because it accounts for the external costs of polluting and depleting common goods.

The concept of double materiality for measuring the sustainability in business and finance is at the heart of the EU’s Sustainable Finance Plan. It is also central to the achievement of the UN SDGs and the climate goals of the Paris Agreement.

Figure 3: The two faces of materiality

Source: Robeco, 2023.

Get the latest insights

Subscribe to our newsletter for investment updates and expert analysis.

Conclusion

The Tragedy of the Commons would be solved if companies began to financially internalize the full costs that their operations and supply chains pose to society and the environment. Unfortunately, although conceptual frameworks such as the doughnut economy and planetary boundaries are helpful for framing the problem, there is still a lack of functional tools to help investors practically address external costs in their investment research and valuation models.

Given the difficulty of assigning a monetary value to things like human life or access to clean water, rigorously applying sustainability to industries, companies and investments will be a thorny challenge for years to come.

Footnotes

1Johan Rockström, chief scientist on the team that developed the Planetary Boundaries framework and a pioneer in sustainability, was awarded the 2024 Tyler Prize, the ‘Nobel Prize for the Environment’.

2UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022.

3Global Footprint Network, Overshoot Day Initiative. Earth Overshoot Day 2022 Nowcast Report.

4https://www.un.org/ sustainabledevelopment/sustainable- consumption-production/

5L. Persson, B. M. Carney Almroth, et al. “Outside the Safe Operating Space of the Planetary Boundary for Novel Entities”. Environmental Science & Technology. 2022, 56, 3, 1510-1521. An updated study, “Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries,” published in a division of Science in September 2023, added freshwater use to growing list of breached planetary processes.

6“Linking planetary boundaries to business”, University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership. https://www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/system/files/documents/

7“A Safe and Just Space for Humanity: Can we live within the Doughnut?”. Oxfam Discussion Papers. 2012; “Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist.” 2017. Random House Publishing.

8The Earth Commission, Global Commons Alliance

9Rockström, J., Gupta, J., Qin, D. et al. “Safe and just Earth system boundaries.” Nature. 2023.