Qui sommes-nous ?

Ravis de faire votre connaissance

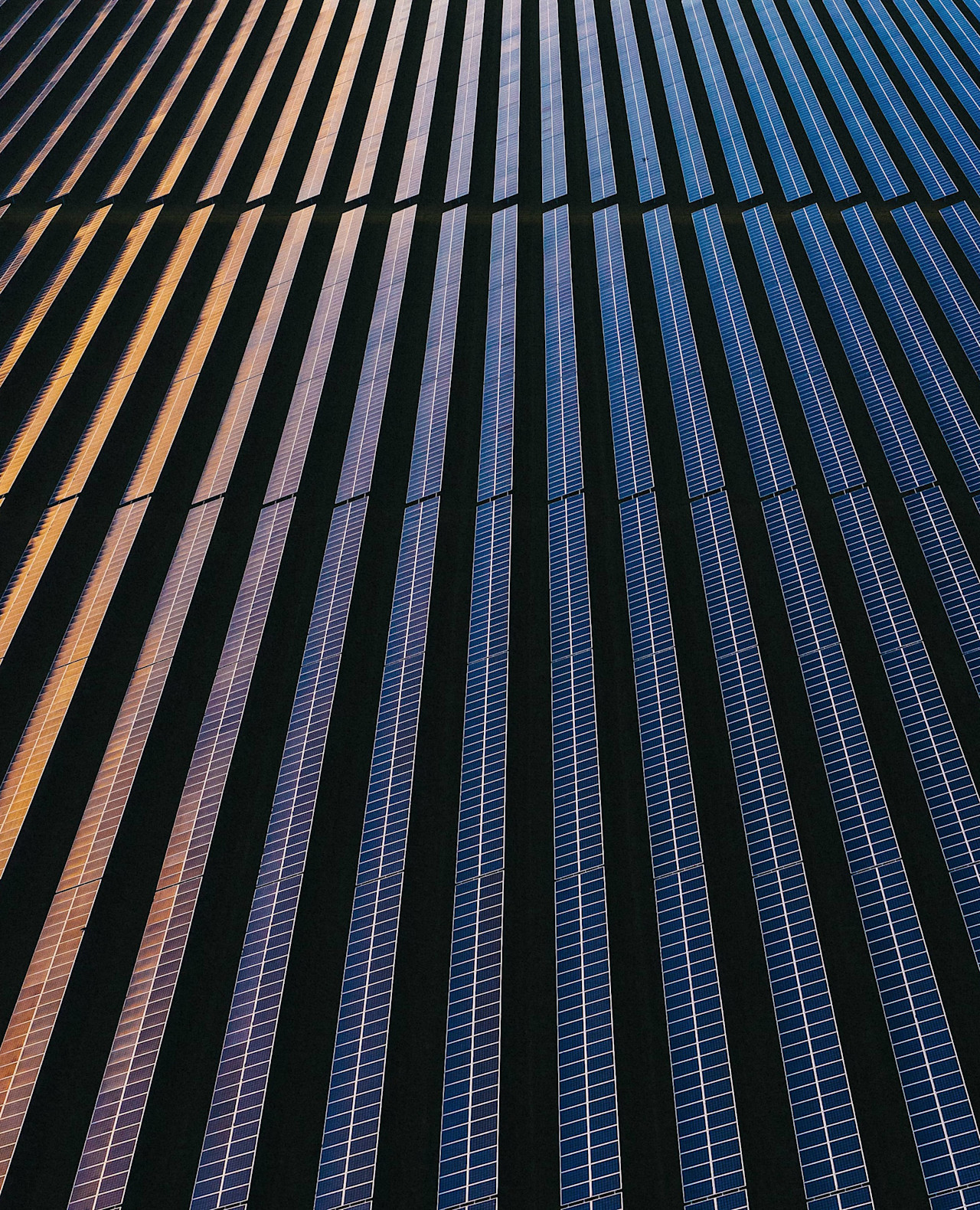

En tant que gérant d'actifs mondial, nous adaptons nos solutions à vos besoins. Nous sommes animés par une curiosité insatiable, une exigence de rigueur dans nos analyses et une passion indéniable pour la durabilité, et nous vous guiderons vers des stratégies révolutionnaires en matière d'investissement actif.

Vous souhaitez investir pour combler vos besoins actuels et futurs ? Nous avons le même objectif en commun : faire en sorte que nos investissements contribuent au bien-être de notre planète et de la société humaine. Ne gardez pas cette conversation pour vous : parlez-en à un collègue.

Perspectives annuelles

Perspectives annuelles Les ETF actifs Robeco

Les ETF actifs RobecoDes ETF actifs pour les investisseurs d'aujourd'hui

Nos derniers articles

Opportunités d'investissement

Nous vous présentons volontiers certaines opportunités sélectionnées par nos experts.

A taste of our products

QI Global Developed 3D Enhanced Index Equities

Approche factorielle systématique et durable comme alternative à la gestion passive

Emerging Stars Equities

Investissement concentré et sans contrainte dans les meilleurs titres d'Asie

Credit Income

Viser des revenus réguliers en investissant dans des entreprises qui contribuent à la réalisation des ODD

Climate Euro Government Bond UCITS ETF

Une nouvelle solution d’investissement qui aligne le portefeuille de la dette souveraine sur l'action climatique