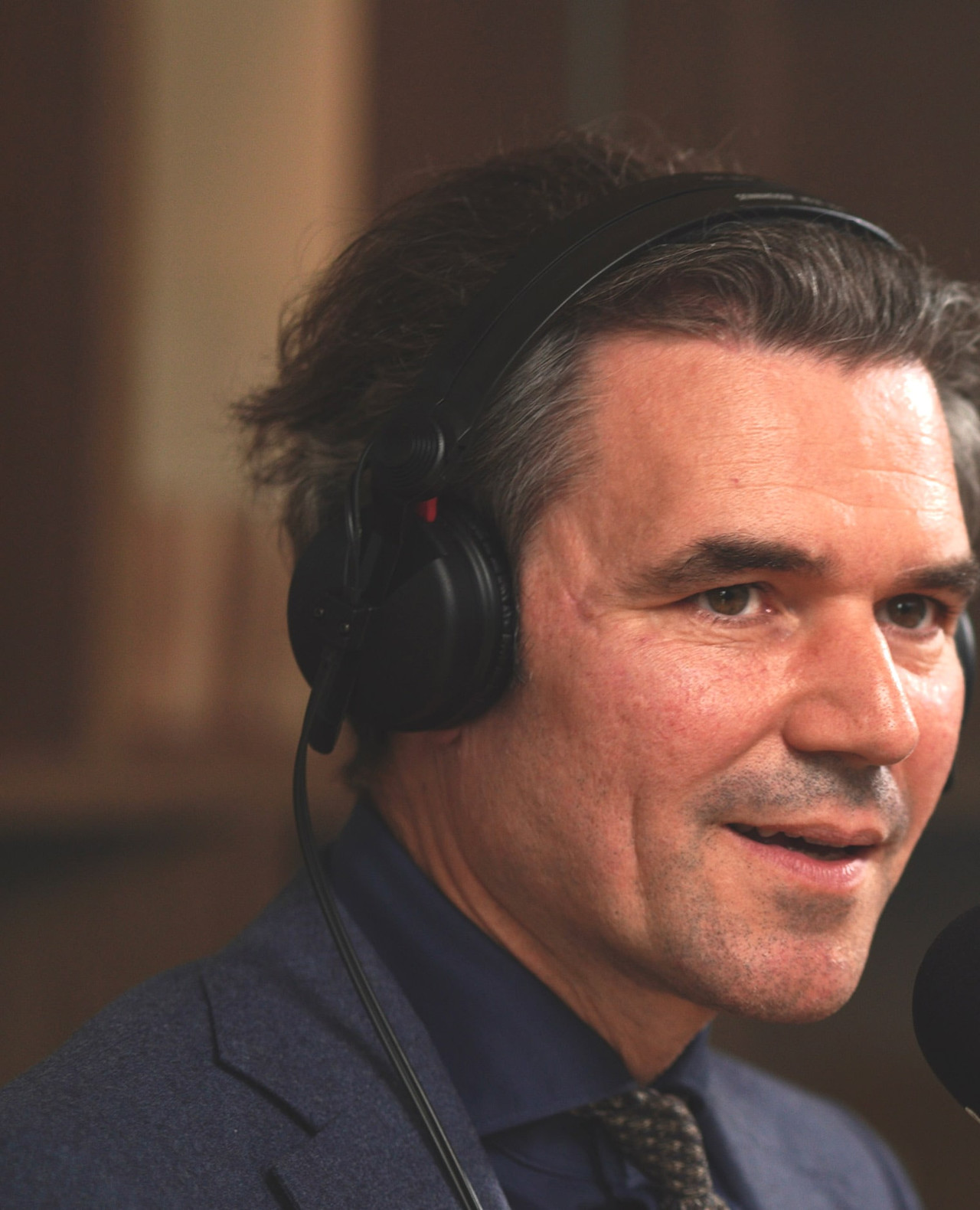

Visie

Welke richting gaan de markten op en wat zijn de gevolgen daarvan? Dat is voor elke beleggingsprofessional de moeilijkste vraag. Dat vraagt om robuust onderzoek en inzicht, zodat werkelijk begrip ontstaat. Daar stoppen we niet voor niets zoveel energie in. Want van het delen van kennis worden we allemaal beter.