SI Debate: How vain, without the merit, is the name?

This famous quote from Homer could not be more applicable to sustainable investing. The ancient Greek poet suggests that the mere presence of a name, without substance, holds little value. It goes into the essence of authenticity and integrity, highlighting the importance of substance over superficiality.

Summary

- Regulatory guidelines aim to make clear how sustainable a fund really is

- It’s not a perfect science, as seen with pursuing engagement and transition

- Robeco’s review of its own sustainable funds led to several name changes

The same philosophy can be used about investment strategies that start with the word ‘Sustainable’. Ensuring that funds billed as being sustainable do what they say has been the focus of regulators and the investment industry itself for many years.

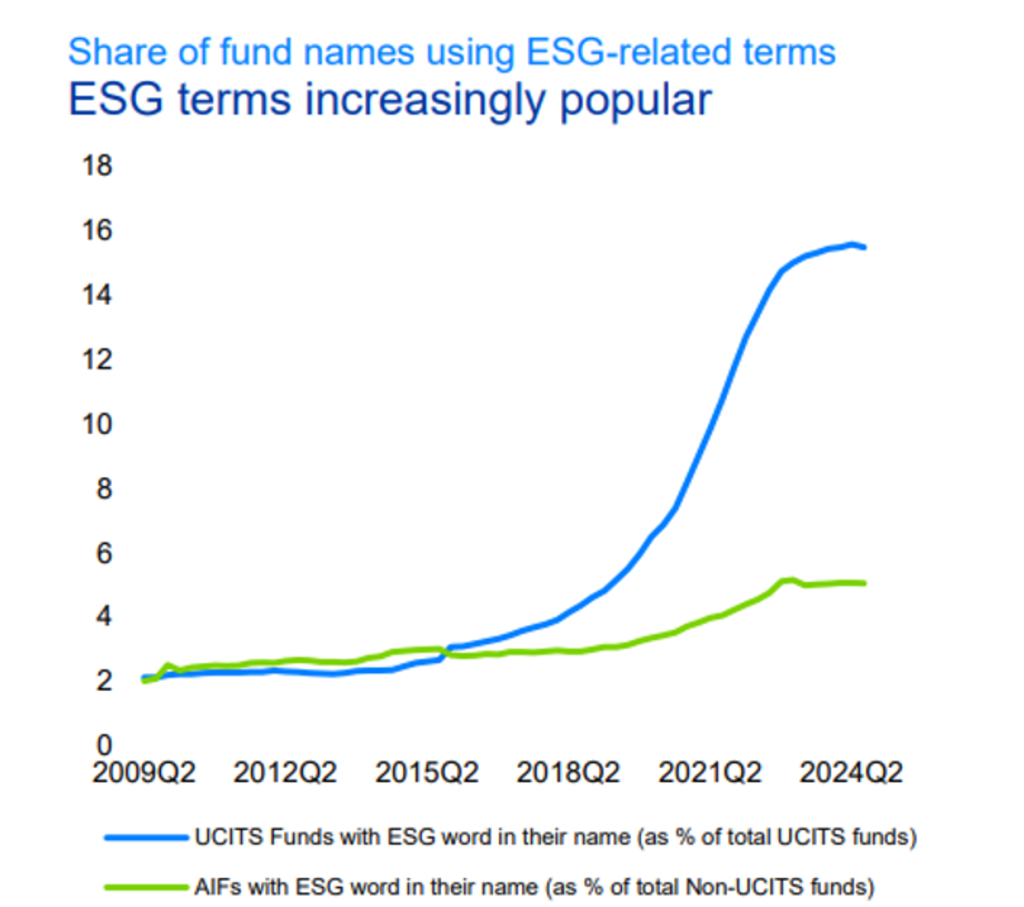

It’s certainly an attractive moniker – research shows that products with the word ‘sustainable’ in their name have attracted greater inflows, in the same way that products labeled as ‘organic’ or ‘free range’ fly off the supermarket shelves. This can be seen in the chart below.

Figure 1: What’s in a name? Adding an ESG term made some funds more popular

Note: Share of UCITS and AIFs domiciled in the EU whose name includes at least one ESG-related word, relative to all funds (respectively) domiciled in the EU, in %. Sources: ECB, ESMA

This kind of labelling led to some being accused of greenwashing, particularly where a fund could include a bare minimum of ESG-related factors, such as making a few exclusions, and then claim it was sustainable. In a bid to avoid misleading the public, the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and the UK’s Sustainability Disclosure Requirements (SDR) laid down rules for fund labeling, while the European Securities Market Association (ESMA) produced guidelines for the use of ESG terminology in fund names.1

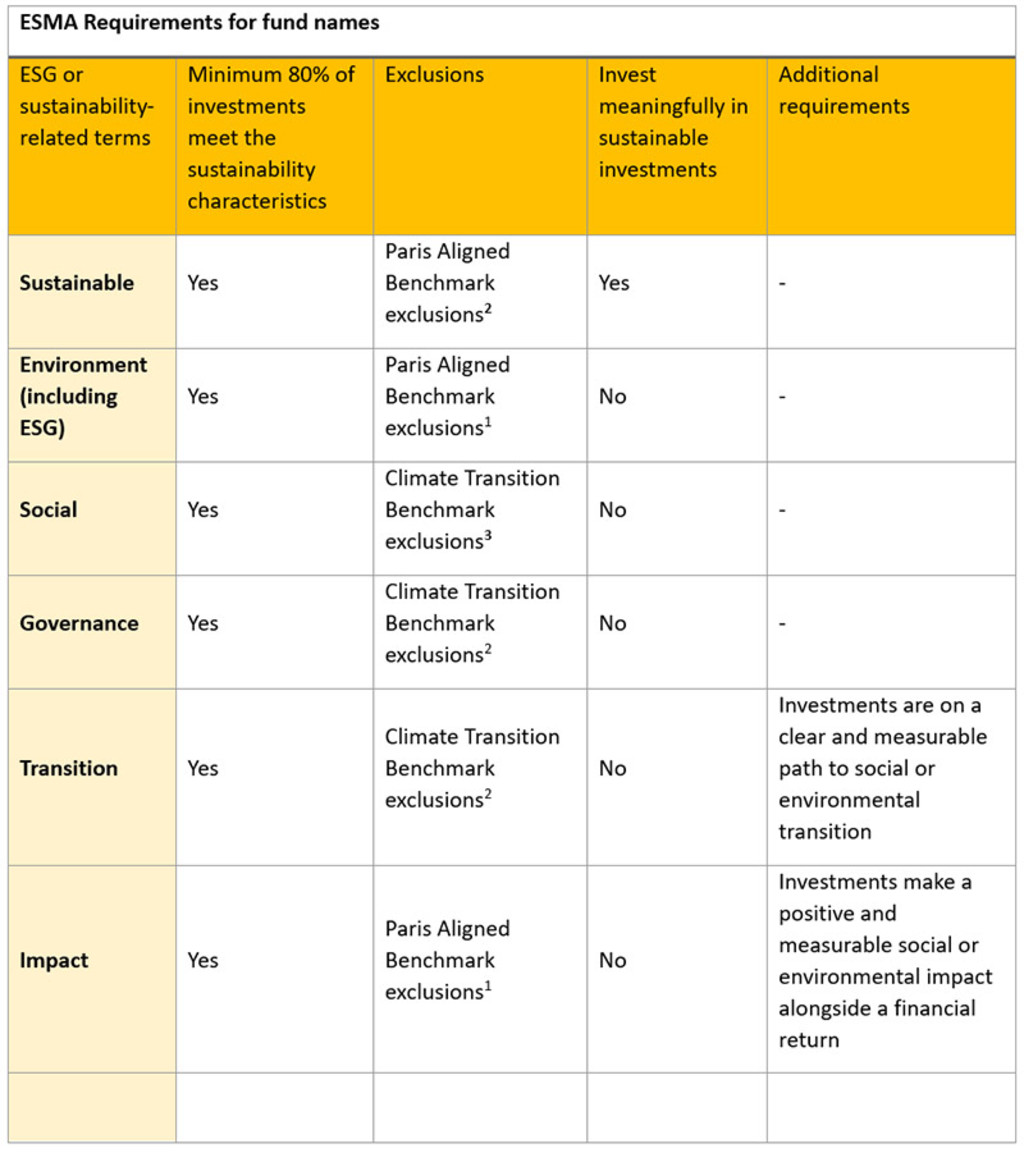

Under ESMA, funds using ESG or sustainability-related terms should have 80% of their investments in securities that meet clear environmental or social characteristics, or sustainable investment objectives. This aims to ensure that fund names accurately reflect the objectives, policy and strategy of the fund. The table below shows the guidelines that are listed for specific naming conventions:

Applying it in the field

How all this is interpreted and applied has largely fallen to asset managers in making sure their products accurately reflect sustainability – such as whether they pursue decarbonization, Paris alignment or other metrics. So, how is it working? Are asset managers honestly applying the guidelines, or is it still a bit of Homer’s adage of ‘a name being vain’? Despite the stricter regulation, it’s still up to the industry to determine:

Whether 80% of investments meet the sustainability characteristics;

What “meaningfully investing” in sustainable investments actually means; and

How to measure and report on the additional requirements for impact and transition.

The most prescriptive guideline relates to exclusions of controversial weapons, tobacco and violations of global standards on human rights. In addition to this, fossil fuel exclusions are also mandatory for funds claiming to be sustainable, environmental, or to be making an impact.

Preliminary analysis showed that funds claiming to be sustainable still often invest in names that should be excluded according to the guidelines. Morningstar estimates that most of the 1,600 sustainable funds were holding at least one stock that was in potential breach of the exclusion rules. About 70% held fewer than five stocks that could potentially violate the exclusion rules.

This means that for roughly 30% of the funds, the possible investment implications could be large. For fund managers there were two options: to either change the name of the product, or change the investment process to fully apply the guidelines. This had some implications for us at Robeco, where we’ve always had a determined approach to have a convincing sustainable offering, but also need to ensure we follow the latest regulations or guidelines.

Keep up with the latest sustainable insights

Join our newsletter to explore the trends shaping SI.

Robeco’s approach

At Robeco, 23% of assets under management are managed using strict sustainability criteria. We found that our sustainable products were already largely aligned with the guidelines and its meaningful sustainable investment requirements, where we defined ‘meaningful’ in principle as having a minimum of 50% of investments according to positive scores using our SDG Framework.

The funds were also aligned with exclusions on controversial weapons, tobacco and global standards breaches. However, some of our mainstream funds labeled as being sustainable did not have an outright exclusion on fossil fuels. Our policy has been to exclude fossil fuel names based on climate criteria and our enhanced engagement program. We believe this to be a smarter way to work toward change in this industry, rather than blanket exclusions.

Were we therefore also falling foul of the guidelines? This is not only an issue for Robeco, but for many other asset managers as well. We found that it was simply not feasible to exclude some fossil fuel names in some strategies labeled as being sustainable – mostly in those with low relative risk budgets, or those promoted to clients as a core building block of their portfolios. In other words, there is no catch-all policy that works for everything.

Two more problematic words – engagement and transition

This led to our own SI Debate about whether strategies should therefore be renamed. The issue is further complicated by our desire to launch funds which focus on two words that are themselves inexorably linked to sustainability – engagement and transition. This brought about a tricky situation where, to quote another philosophical phrase, ‘You can’t do right for doing wrong.’

Engagement strategies are designed to invest in companies that are not sustainable yet, but can be encouraged to improve. The SDG Framework was used to identify these companies that are a work in progress. But we had to remove the ‘SDG’ part of the name because the fund, by definition, invested in companies that were not yet contributing positively to the SDGs, although they have the potential to do so. Subsequently, Robeco Global SDG Engagement Equities was renamed by taking out ‘SDG’.

It proved more straightforward in ensuring that the names of our transition strategies, which were introduced in 2024, corresponded with the guidelines. As with engagement, they likewise target companies that are, by definition, transitioning to a more sustainable business model but are not there yet. This is easier to demonstrate, and so the word ‘transition’ remained in their names.

Impact on the wider market

And it’s not just us. Our research shows that in the wider asset management industry, about 25% of funds changed their names due to ESMA guidance, meaning that for the largest part of the sustainable fund ranges, the name was kept. We also noticed some changes in terminology, for example changing ‘net zero’ to ‘climate’, and moving from ‘ESG’ to the more subjective but less meaningful ‘responsible’.

Morningstar reviewed a much larger universe of over 4,000 EU open-ended funds and found that only about 8% dropped the ESG-related names. About 40% changed the name to ‘screened’, ‘select’ or ‘committed’, suggesting that managers remain keen to market ESG characteristics through fund names, albeit by describing it in a different way.

So, like the transitional companies, it all remains a work in progress. At Robeco, we continue to balance our clients’ goals of return, risk and sustainability through listening to their objectives and tailoring the outcome accordingly.

We have shown the expertise and capabilities to deliver these solutions, and will always be transparent about how sustainable the underlying fund actually is. The guidelines will help, but at the end of the day, it’s about the honest commitment.

Footnotes

1 https://www.esma.europa.eu/document/guidelines-funds-names-using-esg-or-sustainability-related-terms

2 Controversial weapons, tobacco, violations of Global Standards, fossil fuels: >50% revenue in gaseous fuels or electricity generation > 100gCO2/KwH, >10% revenue from oil fuels, >1% revenue from coal, DNSH

3 Controversial weapons, tobacco, violations of Global Standards, DNSH